Astor was born in 1763, to a farming family from a small German town called Waldorf. At 15, he moved to London and began a flute making business with this brother. At 20, he crossed the Atlantic. At 23, he already owned a small colony in Oregon called Astoria and had a thriving fur business: he would buy the fur from trappers in rivers like Columbus or Missouri, and then would take the pacas to the East. At 50, he owned a continental fur monopoly.

He financed expeditions. He helped push the American border further west. He invested his considerable income (he was the richest man in America) in a very specific piece of land of New York: the land between Central Park and Houston Street. This is now known as midtown Manhattan, one of the most expensive real estate areas in the world.

He also pushed his family name into the future (and perhaps into eternity -- so far, his name is still important in New York): his descendants inherited his fortune and became notorious for the way they managed it. His son was a ruthless land owner. His grandson founded the Metropolitan Art Museum and the Astor Library (at the core of 42nd street). One of his great grandsons became British (the Count of Astor). Another one was a science-fiction writer who erected the Waldorf and St Regis hotels. Another one died in the Titanic. Another one ran Newsweek.

The family is better remembered today for the Waldorf-Astoria hotel in New York. Many family members contributed to said project, but were particularly key: William Waldorf Astor, and his aunt Tina. Actually, Tina had very little involvement and it was all mostly William's desire to pester her. Tina hated noise almost as much as she hated people. So William Waldorf located the biggest hotel in the world right next to her house. She moved out.

It pretty much defines this fascinating clan.

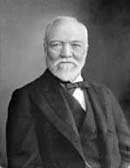

Andrew Carnegie considered himself to be a saint and a moral giant. We'll just say that he was a colorful moralist and that, spiritually, he was not small.

He was born to abject poverty in Scotland -- a country that, for one reason or another, creates a sadder and more abject poverty than anywhere else in the world. He was just a boy when he moved to America. And his luck changed.

That luck would, in fact, lead him to fight in the American Civil War, where he became assistant to the Assistant Secretary of War in charge of military transportation. So Carnegie seized the opportunity to invest in railroads and stenographers. He then copied the British systems to produce steel and set a foundry in Pittsburgh, with Henry Clay Frick as a partner.

Just like Astor, Morgan and Vanderbilt (they would all boast of having the same title), he became the richest man in the world. So he would rest for half a year in Scotland, where he would lament Frick's attitude and style (which, on the other hand, were making him richer) and spend the other half preaching how useful poverty was in building one's character and how sad it was to be rich.

In 1889, he published an article called "The Gospel of Wealth" in a newspaper called The Pall Mall Gazette, where he reached the conclusion that magnates had to improve their communities. And this was no hypocrisy: in the following years he created a foundation and tasked it with "improving humanity and creating world peace". They still need to get back to us on that.

He also financed about 3000 public libraries and research facilities. He also bought all of Frick's shares of the business and stopped talking to him. The man who had made him rich was no longer desirable company.

Henry Vanderbilt understood the importance of good family relations in a capitalistic world.

His father was Cornelius Vanderbilt, who thanks to his family, managed the transition from primary school drop-out in 1805 to the second wealthiest man the U.S. has ever known.

Cornelius used his father (Henry's grandfather) to learn business in the nautical transportation business. His mother lent him the money to buy his own boat. He conquered the famous Staten Island Ferry by putting his brother-in-law in command of the ship. He bought the company a few years later and then put it in the hands of his brother Jacob. It's not that he lost interest in boats after realizing the future lay in railroads. That's where his son Henry comes in.

Henry gained his father's railroad monopoly and vast wealth. But he never gained his trust. A cold, imposing man, Cornelius used to refer to his son as a "blockhead" and a "blatherskite." Henry never dared to stand up to him.

So he took it out on the world. After his father's death, he continued accumulating railroads and trains until he basically owned the New York public transportation system. At one point, he was reminded that public transportation required a certain practical (political) planning and at least a slight interest in what the citizens needed. He then coined the immortal phrase: "The public be damned!"

He constructed a series of delirious mansions, full of towers and battlements, right by the Astor's estate. He single-handedly created Fifth Avenue, with such success that even the Astors moved in them.

None of the mansions have survived.